In this article

From Pairing to Leading

How I Turned AI Into an Engineering Team

Somewhere around November, I realized I had not written a feature end to end in weeks, but I was shipping faster than ever

PRs were landing, the backlog was shrinking, and the work I was doing no longer looked like “software engineering” the way I had internalized it.

Less typing code. More deciding what should exist, defining what “done” means, and reviewing what an AI system produced.

I had moved from pairing with AI to leading it.

The pairing phase is useful, and it does not scale

Most people’s relationship with AI in engineering still looks like onboarding a new teammate. You open a chat, explain the task, guide it, give it small chunks, and keep a close eye on the output. Used that way, it is genuinely valuable. These tools are great at the mechanical parts of the job: refactoring, chasing compiler errors, translating patterns across files, and doing the kind of codebase spelunking that normally costs you an afternoon.

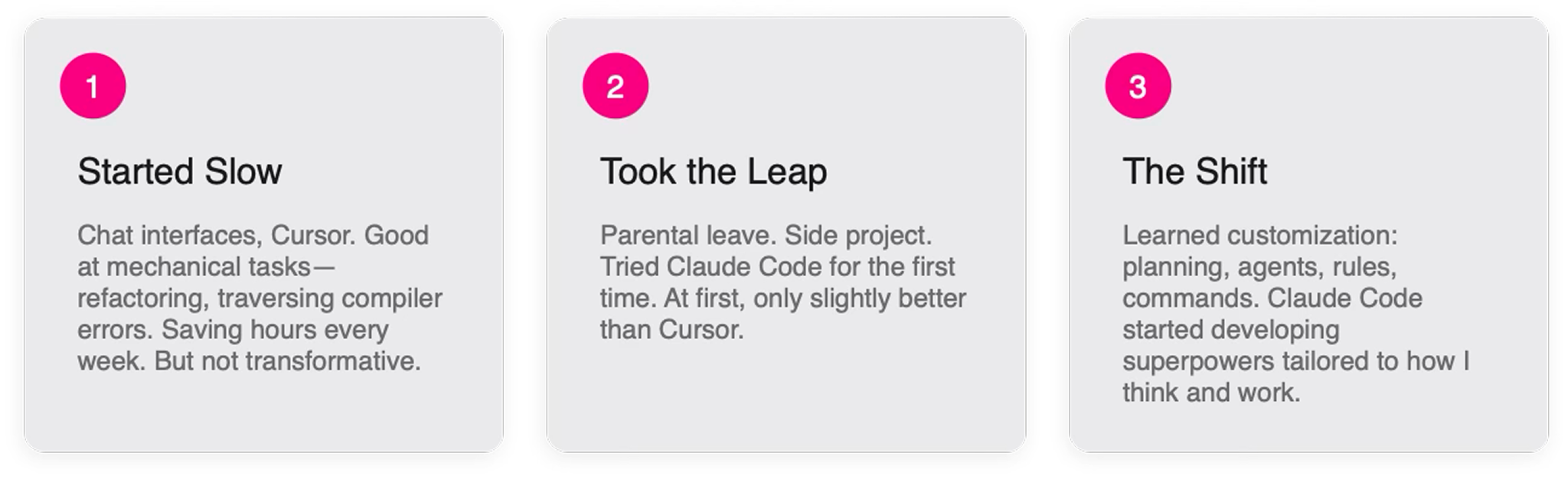

I started there too. I used chat. I used Cursor. I saved hours every week. It was an upgrade.

But it had a hard ceiling.

Every session started from zero. The AI did not remember what it got wrong yesterday, or the architectural constraint you had to repeat in every PR, or the house style your team agreed on months ago. Worse, it would not stop and ask clarifying questions when it drifted. It would just keep going.

So you became the memory. You became the glue. You carried the context the tool could not hold.

And the better you got at prompting, the more obvious it became that the real problem was not “how do I ask better questions.” The real problem was that tomorrow you would ask the same questions again.

The tool did not become a superpower until I made it mine

The shift for me happened in stages.

At first, AI felt like faster autocomplete. Useful, but bounded. Then I went on parental leave and started a side project, and I tried Claude Code seriously for the first time. My initial reaction was underwhelmed. It was slightly better than what I was used to, but not in a way that changed how I worked.

What changed everything was customization.

Not “custom prompts,” in the sense of having a favorite incantation. I mean treating the system like something you can shape: planning workflows, agent roles with scoped context, rules the tool reads every time, and commands that turn feedback into persistent behavior.

Once I started doing that, Claude stopped behaving like a clever intern and started behaving like something closer to a team that understood my expectations.

The tool was not transformative until I made it mine.

Front-load everything

This is the part that feels backwards at first.

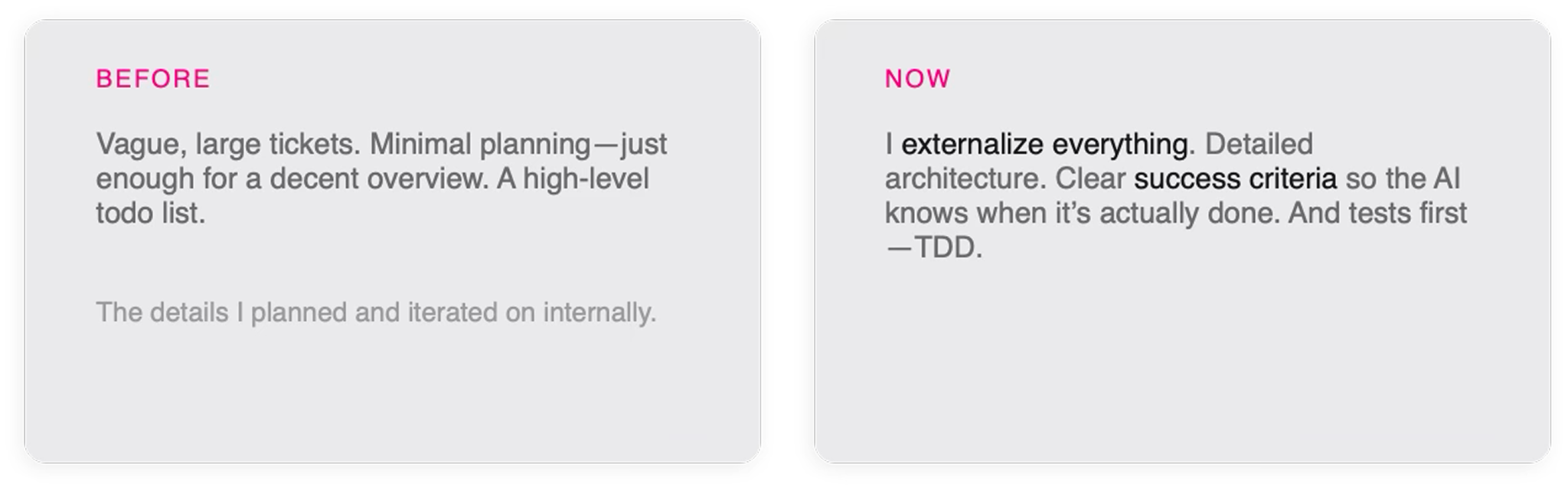

There is a default engineering workflow that most of us fall into because it feels efficient. Tickets are large and a bit vague. Planning is minimal, just enough for a decent overview. The real detail lives in your head and you iterate as you code.

That approach works fine when the implementer is you. It breaks when the implementer is an agent.

If you want an AI to execute well, you cannot keep the real plan in your head. You have to externalize it. You have to write down architecture in a way that is not interpretive. You have to define success criteria that are crisp enough that “done” is not a vibe, it is a testable state. And for me, that meant tests first.

This sounds like it would slow you down. It does, at the beginning. But it shifts the time to the highest leverage place. All the effort you used to spend iterating mid implementation gets pulled forward into planning and defining “done.”

Ironically, working faster meant slowing down at the start.

Once I had a plan, success criteria, and failing tests, execution became almost mechanical. The AI could run forward confidently because it had a contract.

Stop thinking “assistant,” start thinking “team”

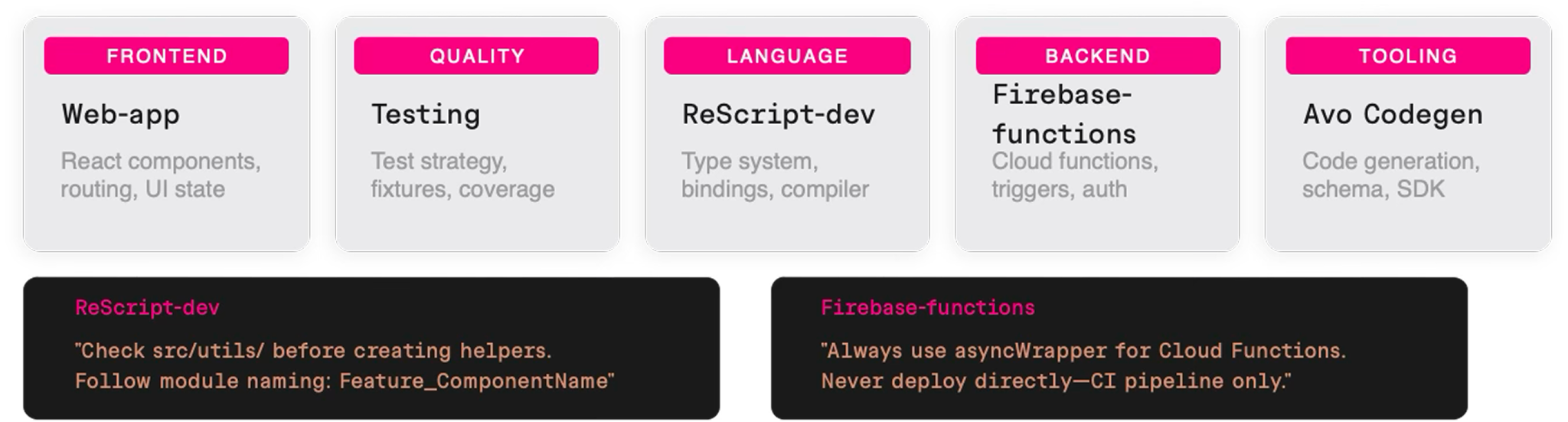

The next step was to stop treating AI as one general purpose thing.

In a real engineering team, not everyone does everything. People specialize. Context matters. Rules differ across domains. The constraints for frontend work are not the constraints for cloud functions. The things you want to emphasize in a codegen pipeline are not the same as what you want to emphasize in test strategy.

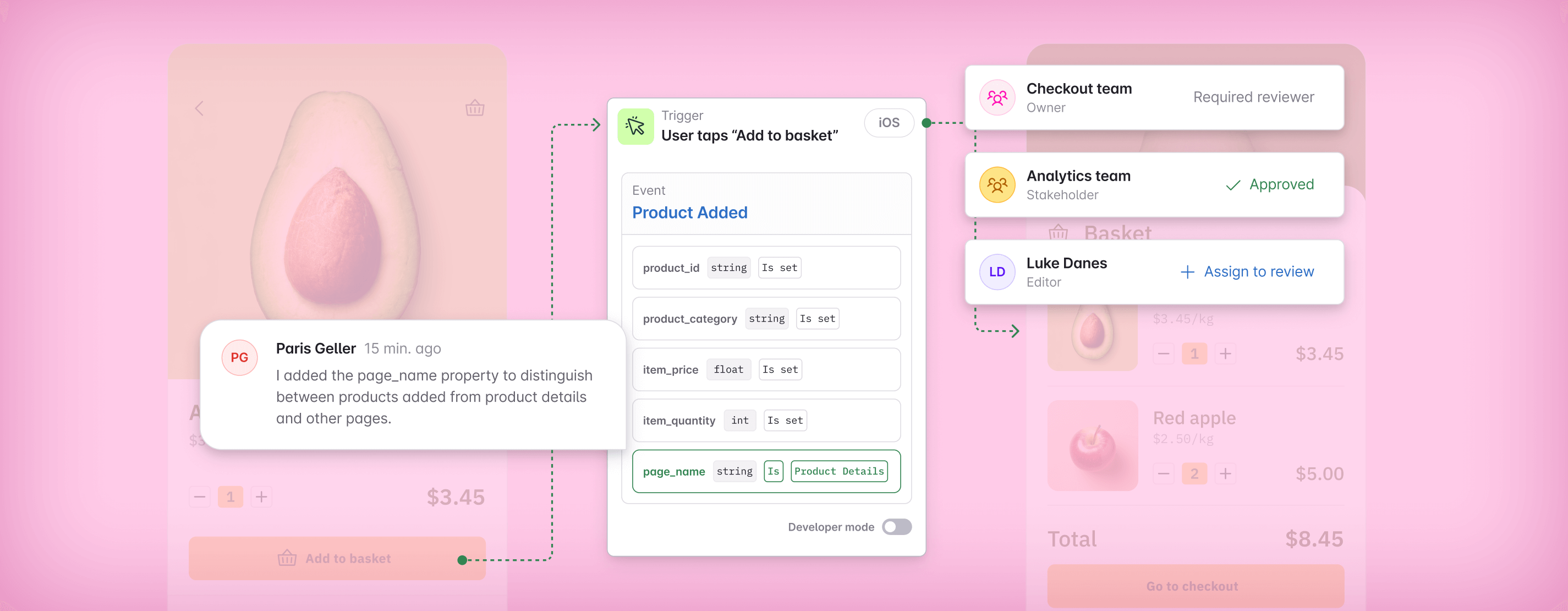

So I built agents that were scoped, each one tied to a specific part of the codebase with its own rules and context. Frontend. Backend. Quality. Language tooling. Codegen.

In practice, this means dedicated agent definitions scoped per domain — each with its own context, rules, and constraints. The frontend agent knows about our component patterns and design system. The backend agent knows about our API conventions and database access rules. They share project-level context, but the rules are intentionally not global. They are targeted.

That reduced drift immediately, because the AI did not have to guess which standards applied. It already knew what kind of work it was doing, and what “good” looked like in that area.

Parallel agents change the shape of a feature

Once you have a real plan and scoped agents, the obvious thing to do is run them in parallel.

The contract between agents is types and tests. I merge the types and failing tests first. Then I dispatch a frontend agent and a backend agent to implement their sides at the same time. The compiler catches interface mismatches. The tests catch behavioral mismatches. I stop being the human router of every tiny integration detail.

For example: when we built the Inspector Debugger, we had to update two codebases — the SDK needed to send event schemas in a new format, and the Inspector API needed to handle that format in a backwards-compatible way. We started by updating the shared types and writing backwards-compatibility tests. Then we created JSON tests that validated the SDK output matched the expected shape, and API tests that used the same JSON as input. The types became the plan. The JSON became the contract. We fired agents in parallel on separate branches across both projects, and had two PRs in two different repositories ready within an hour.

And at that point it becomes hard to deny what is happening.

You are not coding anymore.

You are dispatching and reviewing.

Dev time collapses, planning and review becomes the work

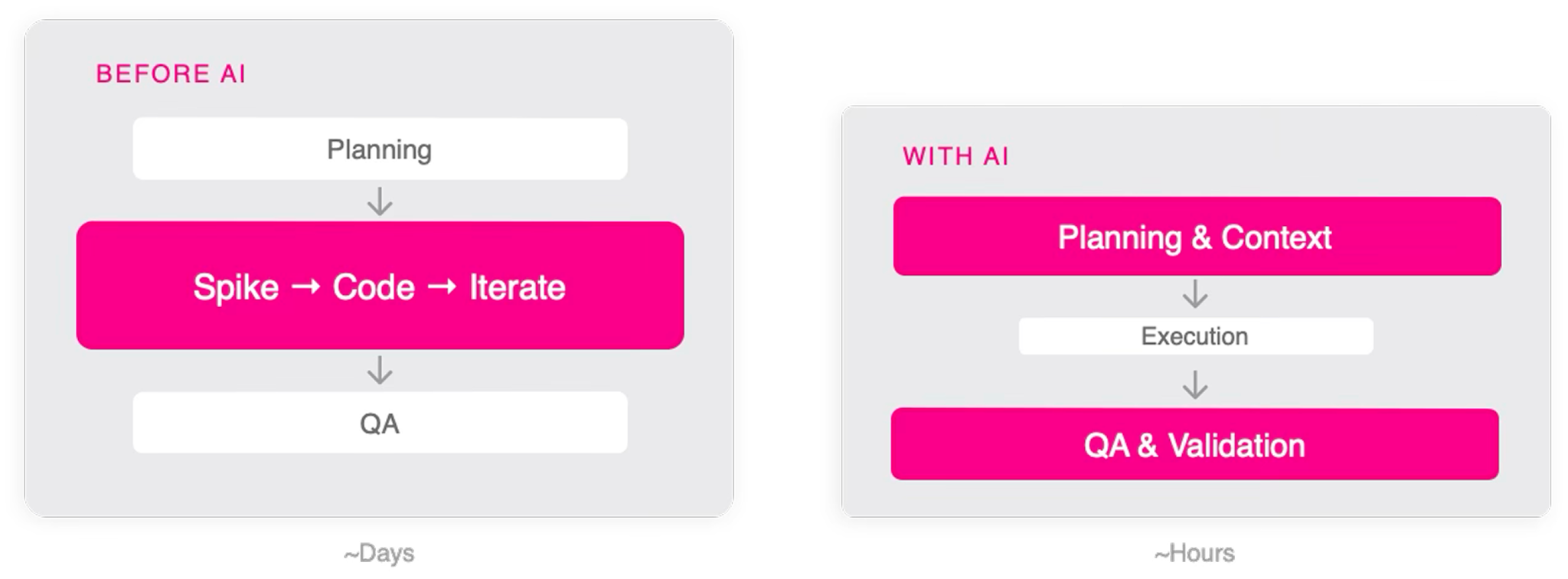

When execution is fast, the timeline of a feature changes.

Before, the arc looked like planning, then a spike, then code, then iterate, then QA. Days disappear in the iterate loop. With agents, that loop compresses dramatically. You spend more time on planning and context, and then execution happens quickly. QA and validation still matter, but the overall wall clock time collapses.

That sounds like a pure win, until you hit the new bottleneck.

Speed without confidence is just faster mistakes.

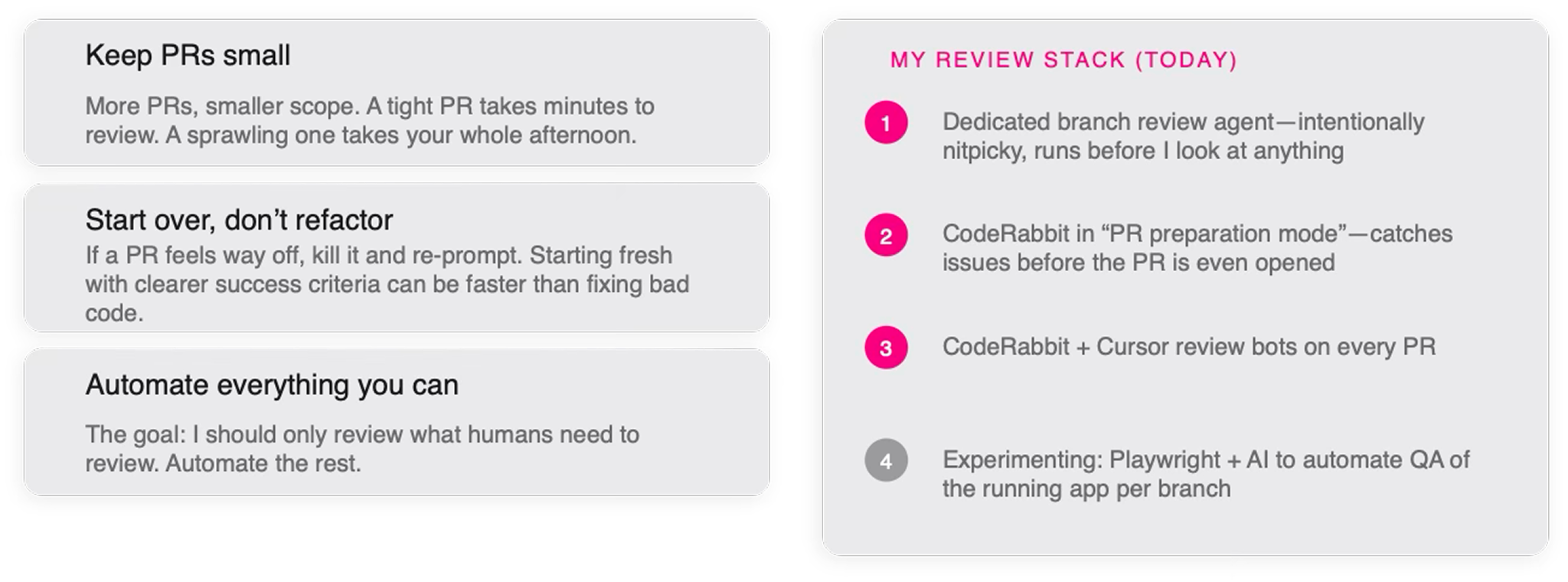

I have not solved the review process. Not fully. We are still swamped with PRs, and if I am honest, it is the limiting factor on how far I can push this workflow without burning out. But I have learned a few things that make it survivable.

Keeping PRs small is non-negotiable. More PRs, smaller scope. A tight PR takes minutes to review. A sprawling one takes your whole afternoon.

I also stopped being sentimental about bad output. If a PR feels wrong at the foundation, I do not refactor it into shape. I kill it, re-prompt with clearer success criteria, and start over. Starting fresh is often faster than rescuing code that was built on a wrong mental model.

And then there is the automation layer. The goal is simple. I should only review what humans need to review. Everything else should be caught before my eyes ever see it.

Right now my stack works in layers. First, the agent itself has hooks that run before it even opens a PR — type checking, lint, and a set of custom validations we have built up from past mistakes. Second, a dedicated branch review agent reads the diff and flags anything that looks structurally wrong: unused imports, functions that duplicate existing utilities, test coverage gaps. Only after both of those pass, the PR hit my queue. By then, the obvious stuff is already handled. I am reviewing intent and architecture, not syntax.

I am also experimenting with Playwright plus AI to automate QA of a running app per branch. This is still frontier work, but it is clearly where the leverage is.

The compounding trick is retros, not prompts

One of the most frustrating parts of the pairing phase is that the AI never learns from you. You correct it, merge the PR, and next week it makes the same mistake again.

So I built a habit, and eventually a command: /retro.

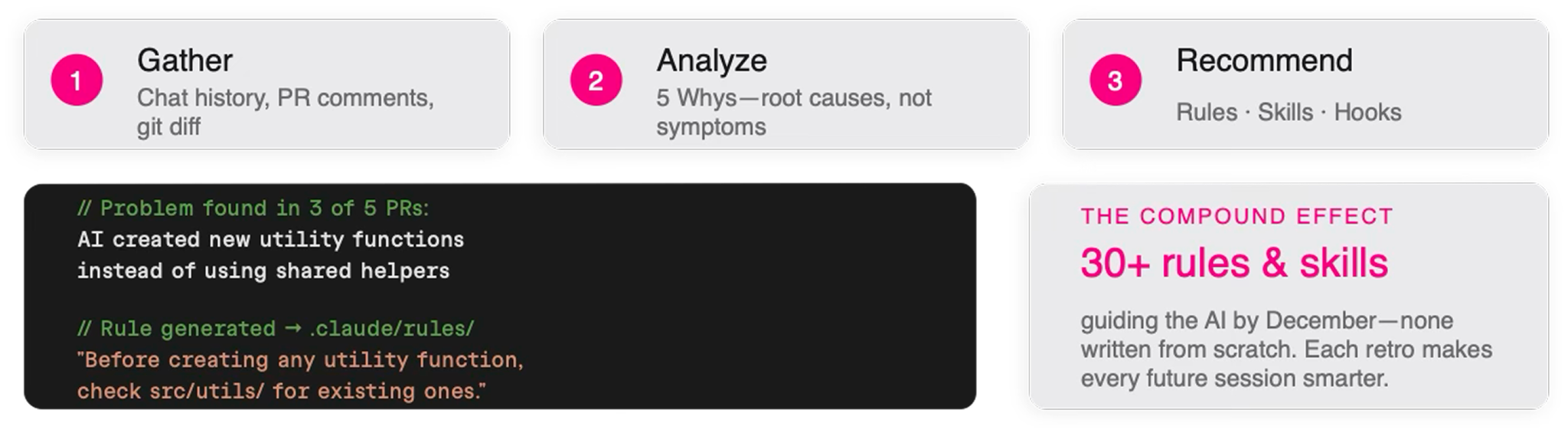

After every merge, I run a retro that gathers the chat history, PR comments, and the git diff. Then it looks for root causes, not symptoms, using a simple 5 Whys style analysis. Finally it outputs recommendations: new rules, new skills, new hooks.

This is where the compounding happens.

If the AI keeps creating new utility functions instead of using shared helpers, I do not just correct it in the PR. I capture it as a rule: before creating a utility function, check src/utils/ for existing ones.

By December, I had over 30 rules and skills guiding my setup. None written from scratch. Every single one extracted from a real mistake. Your mistakes tell you what rules you need.

But rules are not write-only. Around rule 25, I noticed the agents starting to hedge — following one rule while half-violating another. The context window is not infinite, and contradictory guidance makes the AI cautious in the wrong places. So pruning became part of the process: merging overlapping rules, retiring ones the codebase had outgrown, and occasionally rewriting two vague rules into one precise one. The retro does not just add rules. It maintains the system.

Your role evolves, whether you like it or not

There is a moment where you stop thinking, “wow, I am coding faster,” and start thinking, “wait, I am doing a different job.”

The best metaphor I have is being the chef in the window — but the goal is to move past it.

Right now, I am still checking every plate. The endgame is designing the kitchen so that the plates come out right without me standing there. That means better recipes (plans), better prep work (context and types), and better quality control built into the line itself (hooks and automated review). I am not there yet. But that is the direction I want to confidently get to..

In practice, that means breaking problems down, defining success criteria, dispatching agents, and reviewing, rejecting, or approving the output. And increasingly, building the system that builds the product.

An agent says it is done. I check. Something is off. I send it back.

This is the job now.

It does not always go smoothly. The most common failure mode is not bad code — it is code that solves the wrong problem. The agent followed the plan perfectly, but the plan was lazier than I thought. You catch it in review, send it back, and realize the fix is not in the implementation — it is in your own spec. Other times, parallel agents each produce clean PRs that pass their own tests, but diverge in assumptions that only surface when you test them together. The answer is always the same: the planning was not specific enough. The fix is upstream, never downstream.

Start small. Make it real. Start Today.

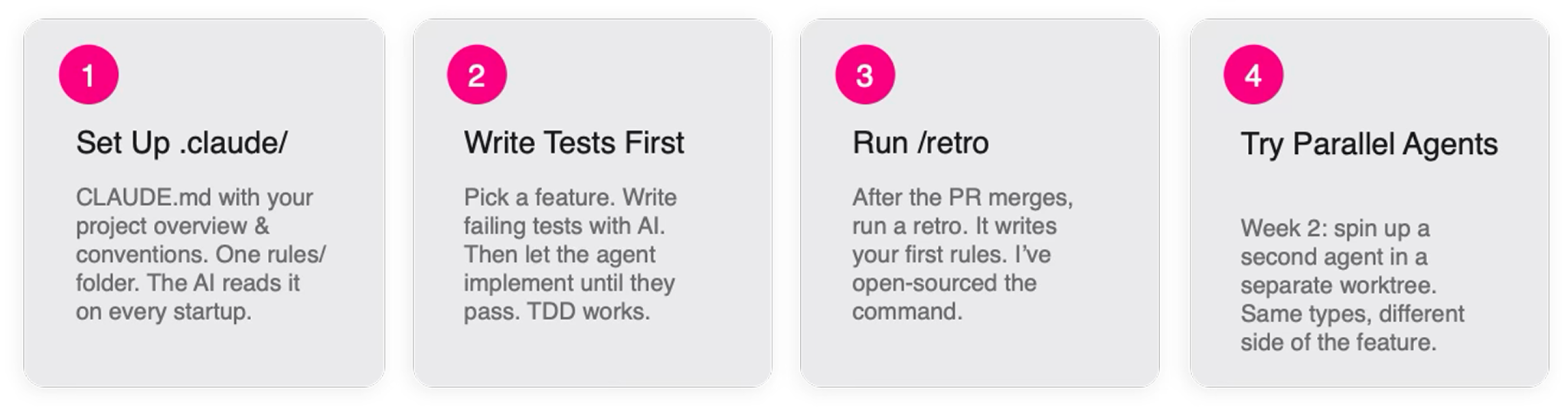

If you want to try this without turning your week into a research project, here is the simplest path that actually works.

Set up a place where your project context and conventions live so the AI reads them every time it starts. Add a rules folder that you can grow over time. Pick one feature and write failing tests first. Let the agent implement it until they pass. When you merge, run a retro and turn whatever went wrong into a rule.

Then, in week two, try parallel worktrees with two agents on different sides of the same feature.

You will feel the shift as soon as execution stops being the hard part.

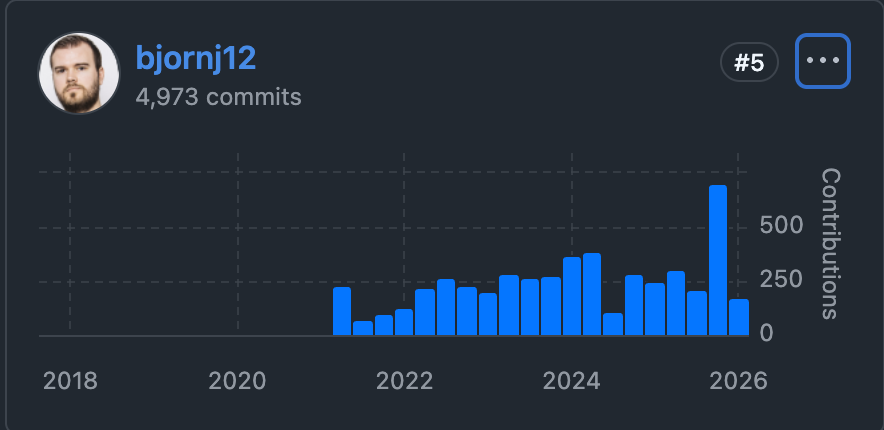

I started experimenting seriously in September. By December, everyone on our team had moved from Cursor to Claude, not because we mandated it, but because the workflow made the value obvious.

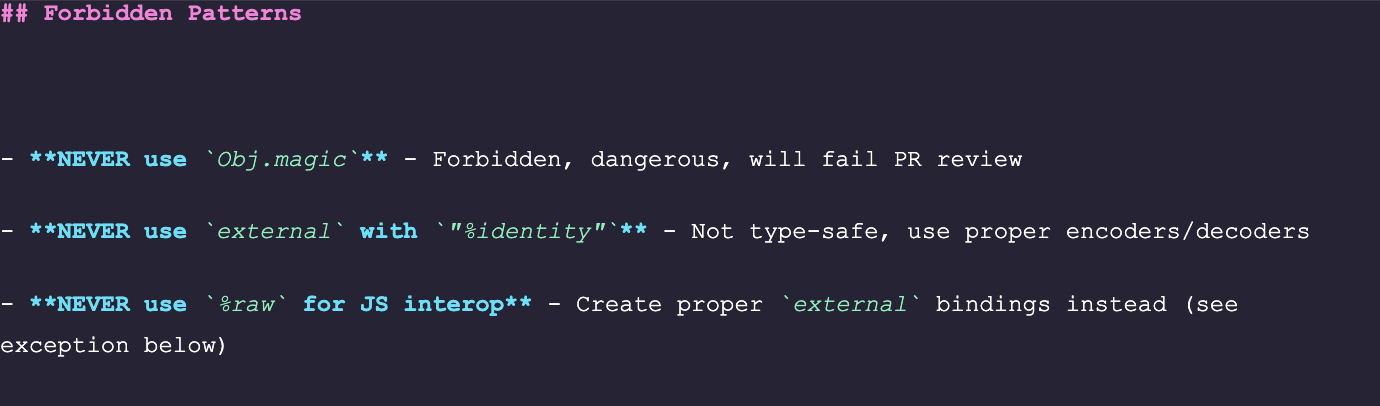

Hooks — small automated checks that run before or after the agent acts, like verifying imports or catching forbidden patterns. Hooks fix the same errors you were manually catching in every PR. Once you have them, you never have to go back to checking by hand.

Every rule you extract, every retro you run, your AI gets a little closer to a teammate.

The learning compounded faster than I expected.

Over time you get a little closer to the part of engineering that matters most: designing systems that reliably produce correct software, consistently, at speed.

Block Quote